Highlights

A Defining Chapter in Mexico’s History

This monument commemorates the Mexican Revolution, an era of Mexico’s modern history that, whilst undoubtedly a dark, violent period with a grim death toll, was nonetheless a transformation of the Mexican state that redefined the nation as a democracy.

The Revolution was sparked in 1910 by a revolt against Porfirio Díaz, a president-dictator who had ruled Mexico for over three decades. Díaz opened the economy to foreign investment, which unleashed an economic boom but also led to widespread poverty and inequality. The fighting rapidly caused Díaz to surrender his grip on power and to flee the country, but with the revolutionaries lacking a single, unifying successor, a decade-long civil war engulfed Mexico.

Some estimates suggest up to a million lives were lost in the fighting of the Mexican Revolution, as various competing factions fought for control of the nation. Stability did not return to Mexico until the 1920s, when the first post-revolutionary governments came to power and the Revolution’s legacy began to emerge.

Mexican democracy was enhanced: a one-term limit to the presidency has been observed ever since. A new constitution separated church and state, enhanced workers’ rights, and tackled the thorny issues of land distribution and mineral rights.

Yet, whilst the post-revolutionary state was more receptive than the Díaz regime to the needs of the poor and of indigenous communities, the Mexican Revolution did not bring about the kind of radical social change seen in the 20th century’s other major revolutions in Russia and Cuba. Arguably, the nation’s social class system saw more continuity than change in the decades that followed the Revolution.

A Striking Monument and Vista

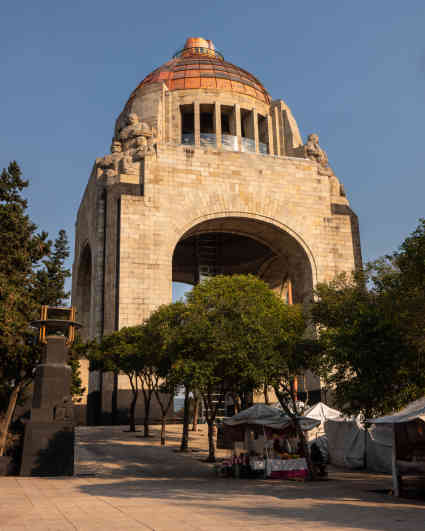

The monument is an architectural wonder. Dominating the Plaza de la República in the heart of Mexico City, it is perhaps the most visible of all the government’s initiatives to cement the Revolution in the national conscience.

Construction of the structure actually began under the Porfirio Díaz presidency, whose dictatorial rule of Mexico came to an end with the onset of the Revolution. Díaz planned to build a congressional palace to house Mexico’s legislative chambers.

The planned palace would have been one of the biggest congressional buildings in the world, with a European neoclassical architectural style not dissimilar to Díaz’s other grand architectural project, the nearby Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Díaz laid the first stone of the congressional building in November 1910, marking the centenary of Mexico’s War of Independence with Spain, but also now known as the month when the Mexican Revolution began.

Construction of the legislative chamber continued for two years, but came to a halt in 1912 as the government’s financial resources were drained by the fighting engulfing Mexico. As civil war raged, the building’s grand steel structure stood abandoned.

It was not until 1933, under the post-revolutionary presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas that an architect, Carlos Obregón Santacilia, proposed converting the planned congressional building into a monument for those who fought in the Mexican Revolution. The European-influenced neoclassical design of the Díaz era was dispensed with, and in its place came an Art Deco design with influences of social realism and indigenous culture.

The monument would also function as a mausoleum for the leading figures of the Revolution. Laid to rest under the monuments pillars are Francisco “Pancho” Villa, Francisco Madero, Venustiano Carranza, Plutarco Elías Calles and Lázaro Cárdenas.

Visitors can learn more about the Mexican Revolution in the museum in the monument’s base, before ascending a glass elevator to the viewing platforms at its summit, which feature a 360 degree panoramic view of this part of Mexico City.

Tickets & Opening Hours

| Monday - Thursday: | 12:00 PM | — |

08:00 PM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friday & Saturday: | 12:00 PM | — |

10:00 PM |

| Sunday: | 10:00 AM | — |

08:00 PM |

Last entrance is 30 minutes before closing time.

The National Museum of the Revolution in the monument's basement has different opening hours.

- The museum is closed on Mondays.

- On other weekdays, it is open from 9am to 5pm.

- At weekends, it is open from 9am to 7pm.

| Tickets (Mexican Pesos): | $ 150 |

|---|---|

| Approx cost in US dollars: | $ 8.00 |

Tickets can be purchased from the ticket office at the entrance to the monument.

The entrance is located on the west side of the Plaza de la República, where there is a large ramp that leads down into the basement of the monument.

Head through the glass doors at the bottom of the ramp, and the ticket office can be found on your left.

Tickets for the museum are purchased separately to the monument. From the monument’s ticket office at the entrance, follow the white arrows leading to ‘museo’ at the back of the monument’s basement.

Getting There

Turibus is a convenient way to tour all of Mexico City’s major sights in a short time. Open-top buses offer great views of the city, while the driver takes care of navigating the city’s chaotic streets.

The Centro Historico route passes the Monument to the Revolution on a circuit that covers many of the city’s major points of interest, including:

- The Zócalo & Metropolitan Cathedral

- Palacio de Bellas Artes

- National Museum of Anthropology

- The Angel of Independence & Avenida Paseo de la Reforma

Tickets and schedules are available online from Viator and Get My Guide

The Monument to the Revolution is a little far from the Centro Historico’s other main points of interest. It is a manageable 20-minute walk from Palacio de Bellas Artes, from where the Centro Historico’s other museums and historic buildings are within easy walking distance.

If you don’t mind a longer walk, the Angel of Independence is a 25-minute walk to the west down Avenida Paseo de la Reforma, from where Chapultepec Park and the districts of Roma, Condesa & Polanco are walkable.

The Monument to the Revolution can be safely reached on bicycle along a number of bike routes that pass close by.

A dedicated bike lane separated from the traffic runs down Avenida Paseo de la Reforma. Heading west, this bike lane connects the monument to Roma, Condesa & Polanco, or head east to the other main sights of the Centro Historico including Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Bikes can be hired by the minute using the ECOBICI app, with hundreds of stations located on almost every major street corner in this region of Mexico City. Download the app, find an ECOBICI station, and unlock any bike by scanning the QR code printed on each bike.

Rideshare apps Uber and Didi are widely used across Mexico City.

Select as your destination:

- Monument to the Revolution, Avenida de la República, Tabacalera, Cuauhtémoc, 06030, Mexico City

For security reasons, avoid hailing taxis in the street in Mexico City. Use rideshare apps like Uber and Didi, which record the driver’s details, or ask your hotel to call a trusted driver for you.

The Monument to the Revolution is located next to several stations on the city’s Metrobus network. The nearest stations are:

-

Plaza de la República on Linea 1: this line passes down Avenida Insurgentes Sur, making it a convenient way to travel to the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods.

-

Amajac on Linea 7: this line passes down Avenida Paseo de la Reforma, passing the major hotels and monuments along this avenue, before terminating at Campo Marte in the Polanco neighborhood.

The nearest station is Revolución on Linea 2. This line is a convenient way to travel to other areas of the Centro Historico, with the Zocalo metro station just 4 stops away.

To travel by public transport from the major touristic centers in Roma, Condesa & Polanco, the Metrobus provides more direct connections than the Metro.

The center of Mexico City is clogged with traffic and difficult for visitors to navigate when driving. But for those choosing to self-drive, there are several parking lots surrounding the Plaza de la República.

On-street parking is also available on the surrounding streets. Make sure to check the hours printed on the on-street parking meters and purchase a ticket, to avoid having your vehicle clamped.