The Rise of a Metropolis

Just outside of Mexico City, the spectacular Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon stand tall over the landscape, remarkably well preserved over the centuries. These vast pyramids reveal the feat of human endeavor that marked the construction of Teotihuacán, an ancient metropolis that dominated this region of Mesoamerica over 1,500 years ago.

Teotihuacán’s roots began as a small hamlet around 150 BC, growing to a moderately-sized city of around 20,000 people by the year 1 AD. The city’s growth then took off. Estimates vary but at its peak Teotihuacán supported a population of over 125,000, the largest city in the Americas at the time. Unlike their contemporary civilizations in Europe, Mesoamerican societies lacked beasts of burden, the wheel or metal. To construct a city as large as Teotihuacán without these aids was a remarkable accomplishment.

Fueling Teotihuacán’s population growth was the intensification of agriculture, with irrigation systems delivering water from the nearby Lake Texcoco. The city became cosmopolitan, drawing in immigrants from other Mesoamerican cultures, particularly from Oaxaca and the Gulf Coast. These different ethnic groups lived in distinct barrios and continued to follow their traditional cultures.

Teotihuacán was a hub for artisans. Workshops across the city crafted knives, cutting tools and figurines from obsidian, sourced from large deposits nearby in the Sierra de las Navajas. Other artisans worked with clay deposits to produce pottery and intricately decorated ceramic figurines.

The city’s craft industry, agriculture and access to natural resources formed the basis of a trade network that exported Teotihuacán’s goods across Mesoamerica. Goods produced in Teotihuacán have been discovered in archeological sites as far away as the Mayan city of Tikal in Guatemala.

Some archeologists speculate that Teotihuacán was a military force which ruled over these far-off territories. Whether through peaceful trade and commerce, or violent conquest and subjugation, Teotihuacán was undoubtedly a dominant force across the region.

The city-state’s most remarkable achievement was the construction of the vast Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, as well as the smaller Temple of the Feathered Serpent. These were built early in the city’s history, between 1 and 250 AD.

The largest of these, the Pyramid of the Sun, is the third largest pyramid in the ancient world. It is an enormous structure: 75 meters (246 ft) high and 225 meters (738 ft) along the base. An estimated 30 million loads of dirt and rubble were excavated from caves beneath the city and hauled to the site. The pyramids of Teotihuacán represent a triumph of arduous manual labor.

Each pyramid was the site of complex spiritual rituals. Archeologists have uncovered the bodies of sacrificial victims within the pyramids, alongside ritual objects and luxury goods which had been left as offerings, such as jade from the Maya region.

Remarkably, Teotihuacán’s urban planners laid out the entire city on a grid system. Archaeologists have uncovered deep significance to the placement of the city’s main structures on this grid, based around the landscape, astronomy, and the Mesoamerican calendar.

For instance, the Pyramid of the Moon is deliberately aligned with the vast Cerro Gordo mountain behind, whilst the Pyramid of the Sun aligns with the sunset on two days that are spaced about one year apart in the Mesoamerican calendar. The central north-south Avenue of the Dead, intersected in the middle by an east-west avenue, aligns with the four cardinal directions which are a central to the Mesoamerican vision of the cosmos. The level of detail that these ancient peoples incorporated into their urban planning, on top of the sheer physical challenges of constructing such a large city, was quite extraordinary.

Mysteries of an Ancient City

Despite decades of study by archeologists, much of the history of this ancient city remains a mystery.

We know little about the origins of Teotihuacán’s people. Perhaps the city was founded by the Totonac people of Veracruz. Others have suggested the Otomí or Popoloca people of the central highlands. Little evidence exists to draw any conclusive link.

We do not know what language was spoken in Teotihuacán. Nor do we know where the city’s residents migrated to following its decline, and which communities they established themselves in. There is some evidence that they spoke Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs (or Mexica). Likewise, similarities in their religion, gods and culture suggest a lineage from Teotihuacán to the Toltecs and Aztecs many centuries later.

To construct a city the size of Teotihuacán and to build vast pyramids out of dirt and rubble, a powerful orator must have led the city’s government who could inspire thousands of followers. Yet we know little about the rulers and leadership of this society.

The city’s layout and architecture reveals that society was starkly divided between rich and poor. Palaces that housed the city’s rulers lined the Ciudadela. Murals suggest that these rulers lived a lavish lifestyle, with costumes made of such imported luxuries as quetzal feathers from Guatemala.

The Pyramids of the Sun and Moon suggest that Teotihuacán was a devout society, whose people would go to great lengths to honor their gods. But beyond this, little is known about their religion.

Archeological findings draw parallels with deities worshipped first by the Olmecs and later by the Aztecs. Murals illustrate a rain god similar to Tlaloc; fire serpents lining the Temple of the Feathered Serpent resemble Quetzalcoatl, and other artwork depicts a female goddess.

Yet these pyramids remain shrouded in mystery. The names we know them by, the Sun and the Moon, can be traced back to the Aztecs, who inhabited this land many centuries after their construction. How the people of Teotihuacán referred to these great monuments, and the identities of the gods that they were built to honor, has been lost to time.

The Collapse of Teotihuacan

By the year 500 AD, Teotihuacán had grown into a metropolis and economic powerhouse but the area’s natural resources were feeling the strain of supporting such a large population.

Demand for timber by the city’s residents had led to widespread deforestation in the valley surrounding the city. Wood was burned for cooking, heating, and to produce lime plaster used in the construction of buildings. The city may have reached a tipping point, where new trees could not be grown fast enough to provide the timber that the city needed.

As trees were cut down across this once heavily-forested valley, soil erosion worsened. The torrential rainstorms of the wet season stripped soil and vegetation from the hillsides, damaging farmlands and clogging the city’s canals and watercourses.

On top of these local environmental challenges, around 536 AD the Earth was in the midst of an extraordinary climatic event. A series of volcanic eruptions spewed ash across the northern hemisphere, plunging swathes of the planet into a dark volcanic winter. In Europe, this climatic breakdown began a long period of economic stagnation which accelerated the fall of the Roman Empire. In the Americas, Teotihuacán would suffer a similar fate. Colder climatic conditions brought drought and desertification that crippled the region’s agriculture.

As the city’s rulers struggled to provide for their citizens, the people of Teotihuacán turned against them. Mesoamerican societies treated their rulers as intermediaries between humanity and the gods. The failure of agriculture and the timber supply, combined with widespread disease and malnutrition, must have signified that this spiritual relationship had broken down.

This was likely the root cause of the uprising that sparked the city’s decline. Buildings along the Avenue of the Dead were torched in a deliberate act of internal rebellion by the city’s residents against their ruling elites. Palaces were burned to the ground. Works of art and symbols of the elites were looted and destroyed.

Scholars disagree on the uprising’s precise date. Different dating techniques place the burning of the city between 500 and 650 AD.

Teotihuacán never recovered from this societal collapse. With the Avenue of the Dead and surrounding palaces in ruins, the ruling class fled to other settlements across Central Mexico. The city’s suburbs continued to be inhabited until the 8th century, but high rates of mortality and emigration hollowed out the population.

With the artisan and obsidian workshops closed, the trade network collapsed and Teotihuacán was no longer an economic powerhouse dominating the region. A power vacuum emerged in Central Mexico and the region fell into a period of war and chaos lasting for several centuries.

The Place Where People Become Gods

For long after the city’s demise, the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon continued to cast a shadow over the landscape, a reminder of the great civilization that had once inhabited this land.

Over six centuries later, the Aztecs (or Mexica) migrated to the central highlands to establish their capital, Tenochtitlan, on the shores of Lake Texcoco, not far from the ruins of Teotihuacán. The ruins of the great pyramids left the Aztecs in awe. Surely, they believed, these must have been built by giants or deities rather than human endeavor. Teotihuacán became a place of great spiritual significance in the Aztec religion.

To the Aztecs, Teotihuacán was the birthplace of the universe, the final location of the Five Suns’ creation legend. The Aztecs believed that the world had been through four previous cosmic ages. Each time, the sun was born and, in turn, destroyed with the world falling into darkness. 52 years after the collapse of the fourth cosmic age, the gods met in darkness at Teotihuacán to decide the world’s fate.

In one version of the creation story, the god Nanahuatzin had the bravery to sacrifice himself in a great fire. By throwing himself into the flames he became the Fifth Sun, rising in the sky to the east in the dawn of the fifth cosmic age, the world that the Aztecs would inhabit.

Another god, Tecuciztecatl, then followed into the flames and emerged as the moon. An eagle and jaguar also entered the fire, and would be honored by the Aztecs as great warriors. Consequently, the ritual of self-sacrifice became a core belief in the Aztec faith.

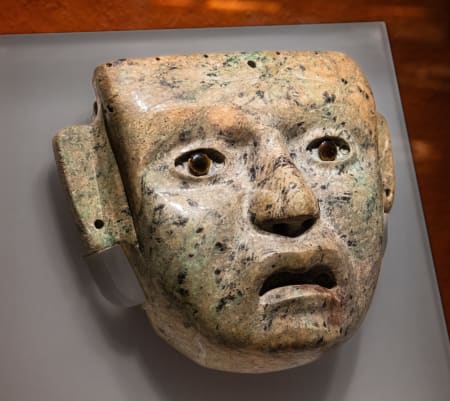

The Aztec Emperor Moctezuma made several pilgrimages to the pyramids at Teotihuacán. The Aztecs were, in fact, the first archeologists to explore the site. They uncovered many works by the city’s artisans, including ritual masks. These were transported to the Templo Mayor in the heart of their capital Tenochtitlan, where they were placed as offerings to the gods.

We will never know the name that the residents of Teotihuacán used for their city, as their language has been lost to time. The name that we know the city by was chosen by the Aztecs, who named this sacred place in their Nahuatl language.

The name refers to the city’s role in the Five Suns creation legend. Teotihuacán is “the place where people become gods”, or simply, the place of the gods.