Since its discovery by archeologists in the 1970s, the Templo Mayor has drawn visitors from around the world, eager to glimpse at the last remnants of the great city of Tenochtitlan, the political and economic powerbase of the Aztec Empire and the spiritual center of their universe.

A visit begins with a walk through the archeological site, where decades of challenging excavations have unearthed the remains of the Templo Mayor and surrounding buildings of Tenochtitlan’s ceremonial center. After this, visitors can explore the Templo Mayor Museum, home to a wealth of Aztec and other pre-Columbian artifacts discovered buried below Mexico City's historic center.

This guide will walk you through each stage of a visit to the Templo Mayor Museum, providing a deeper insight into the society, economy and religion of the Aztecs (a pre-Columbian people also known as the Mexica) and explaining the significance of each section of the museum, room by room.

The Ruins

Constructed in phases over several centuries, by the time of its destruction the Templo Mayor was a remarkable 45-meter high pyramid with dual shrines to the gods Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc on top. Sadly, excavations revealed little of this final era, as the stone was taken from the temple’s ruins for the construction of colonial buildings.

The walk through the ruins therefore reveals earlier stages of the temple’s construction, as well as some of the surrounding buildings.

Walking through the ruins, many of the best preserved elements will stand out. There are remarkable stone sculptures of snakes, a frequent symbol of the god Huitzilopochtli, as well as sculptures of frogs likely dedicated to the rain god, Tlaloc.

One of the most striking archeological finds is a rack of over 200 stucco-covered skulls, known as a tzompantli. These skulls, perhaps of warriors or captives destined for sacrificial ceremonies, formed part of a larger monument, Huey Tzompantli. This structure was known only from the writings of the conquistadors until archeologists discovered the skull fragments in 2015. The wall was placed on the north side of the temple in reference to the region of the dead, Mictlampa.

The path through the ruins leads to the House of the Eagles, a well preserved building where an elite band of Aztec fighters, the Eagle Warriors, came to perform rituals.

Room 1: Archaeological Background

After exploring the ruins, the path leads into the Templo Mayor Museum, which houses a remarkable collection of over 7,000 artifacts collected from the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

The first room, Archaeological Background, charts the many excavations that took place at the site. These began in the latter years of the colonial period, but intensified after 1978 with the launch of the Templo Mayor Project.

A map at the room’s entrance illustrates the scope of these archaeological discoveries, spread across the Zocalo over the course of two centuries.

Some of these findings are on display in the room. These include a sculpture of a golden eagle that was used as a cuauhxicalli, a large bowl where offerings were placed during religious ceremonies. Another highlight is a stone statue of Xolotl, the god of fire and lightning, depicted here with a dog’s head.

Room 2: Ritual and Sacrifice

Aztec society was constructed around an ideological and religious system that encouraged war and sacrifice.

This was motivated, in part, by religion: warriors believed that by dying through war or sacrifice they could repay the gods for their mythical sacrifice that was the origin of life in the Aztec universe. It was also an economic necessity: Tenochtitlan depended on the expansion of territory to collect tributes from conquered lands.

This room showcases a range of objects recovered from the Templo Mayor site that were used by the Aztecs for warfare and religious rituals, including sacrificial ceremonies.

Artists and musicians brought beauty and spectacle to rituals and ceremonies. This can be seen in a set of funeral urns, where exemplary artistry can be seen in the design. And there is a wide range of musical instruments that evidently were performed at ceremonies, including flutes, conch shells and drums.

Rituals at times involved self and human sacrifice. On display on this room are several tecpatl face knives used for human sacrifice, as well as awls used for extracting blood that was offered to the gods in self-sacrifice rituals.

Room 3: Tribute and Trade

As the Aztec Empire grew, it became adept at establishing trading routes and extracting tribute from subjugated populations. Tribute and trade powered the economy of Tenochtitlan and provided the riches found in the Templo Mayor.

This room is filled with artifacts whose origins have been traced to the empire’s far reaches, that were taken to Tenochtitlan through either trade or tribute. There are several fine pieces made from obsidian and tecalli stone, sourced in deposits across the central highlands, as well as artifacts showcasing the differing styles of the Gulf and Pacific coasts, the Mixtec style of Oaxaca and the Mezcala style of Guerrero.

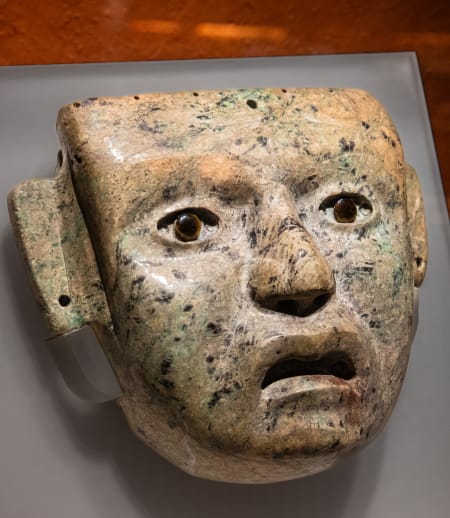

The Aztecs held great reverence for the indigenous cultures that preceded them, collecting historic artifacts from conquered territories to display in the Templo Mayor. The oldest item on display is a mask from the Olmecs: around 3,000 years old today, it predates the Templo Mayor by over two millennia.

The ancient city of Teotihuacán was considered sacred by the Aztecs. This room showcases many artifacts influenced by the style of Teotihuacán, as well as an elegant green stone mask produced by the people of Teotihuacán over 600 years before the Aztec’s rule, who recovered and preserved it in the Templo Mayor.

Room 4: Huitzilopochtli

On top of the Templo Mayor stood two shrines, one of which was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, the patron god of the Aztecs.

According to myth, a divine vision from Huitzilopochtli revealed the location where Tenochtitlan would be founded by a group of his followers migrating to a new homeland. And as the god of war and the sun, Huitzilopochtli’s symbolism was highly relevant to a society built upon conquest, with an economy reliant on extracting tribute.

Although Huitzilopochtli is not depicted himself, the Templo Mayor was filled with objects which honor the god by representing war. These include an impressive stone statue of an Eagle Warrior, an elite and feared league of soldier, as well as a xiuhcoatl sculpture, a fire serpent believed to be Huitzilopochtli’s weapon.

Other deity closely related to Huitzilopochtli also feature in this room. The most impressive artifact is a giant circular monolith of Coyolxauhqui, a discovery that in 1978 prompted the multi-year excavation of the Templo Mayor site.

Coyolxauhqui was the goddess of the moon who, according to myth, was slayed by Huitzilopochtli during the Aztec’s migration to Tenochtitlan. The monolith depicts the body of the goddess in pieces having been thrown down a hillside after losing this battle. Due to its size, the monolith is viewed from a balcony which overlooks it on the floor below.

Room 5: Tlaloc

The second shrine of the Templo Mayor was dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain, water and fertility.

Tlaloc was a god of special significance because of the importance of agriculture to the Aztec economy. He was believed to bring the rains that harvests depend on.

Many of the findings in the Templo Mayor depict the face of Tlaloc. The most impressive artistry can be seen in a large blue pot with a carving of the god’s face. Tlaloc was believed to store water in pots high up on hills. The pot represents the belief that rain was spread over the earth by tlaloques, assistants of Tlaloc, breaking pots of water with sticks.

There is also a remarkable brazier carved in the shape of Tlaloc, which once formed part of the temple’s base.

Many of the offerings to Tlaloc in the Templo Mayor are designs linked to water or the sea. These include a large sculpture of a conch shell, smaller carvings of fish, as well as stone frogs linked to Tlaloc because their croaking was considered an announcement of the coming of the rains.

Room 6: Flora and Fauna

Nature and wildlife was of special significance to Aztec religion. Many Aztec images of animals present them as close to the gods and, in some cases, the gods were depicted with animal traits or could appear in the form of an animal.

This spiritual significance meant that the bodies of animals were frequently used as offerings to the gods in the Templo Mayor. This room displays the variety of animal and plant species discovered in archeological excavations. With the help of biologists, these demonstrate the Aztec Empire’s geographical range and the extent of their interactions with nature.

Wildlife was brought to the Templo Mayor from nearby in the central highlands. Among these offerings are an eagle, mountain lion, wolf, snake and hummingbird.

Many species were also brought to Tenochtitlan from further afield. Marine life was taken from the coasts, including a stingray and sharks’ teeth. Remains of rainforest animals were also discovered, which is remarkable given the challenges of capturing and transporting wildlife across this terrain. Crocodile, jaguar and toucan bones are on display in this room.

Room 7: Agriculture

The Aztecs were a sophisticated agricultural society and farming around Tenochtitlan was highly developed. This room displays some of the tools used for agriculture and explains their advances.

There is a look at chinampas, an intensive system of agriculture that fed Tenochtitlan’s large population by enabling year-round cultivation on a series of shallow, manmade islands. The room also features a reproduction of the vast Tlatelolco market where agricultural goods were traded, the scale of which left the conquistadors in awe.

Given the importance of the harvests for their survival, the Aztecs worshipped many gods related to agriculture. The rain god Tlaloc was the most important, but it was believed that several other figures also helped to bring about a strong harvest.

This room contains statues and artifacts related to these gods. Highlights include a vase of Chicomecoatl, the goddess of ripe maize, and a carving of the face of Xipe Totec, a god also linked to maize as well as war.

Room 8: Historical Archaeology

The museum’s final room traces archaeology through Mexico’s modern history, from the defeat of the Aztecs by the Spanish conquistadors in 1521 up to the 20th century.

This room explores how the introduction of European culture, architecture and materials began to influence Mexico over time.

Various displays chronicle the introduction of European materials, such as glass and plastic. Influences also came from further afield. Tiles originally came to Spain during the Arab occupation of the Iberian Peninsula. China porcelain was brought to Mexico across a Pacific trade route with the Spanish colony of the Philippines.

The introduction of the Roman Catholic religion had a major impact on Mexico. Many artifacts here feature Christian iconography or ceremonies, such as the cross or the Christmas nativity.

Despite the destruction wrought by the invading Spanish army on the Aztec Empire, it is emphasized that the Aztec culture did not disappear with the fall of Tenochtitlan. Rather, the mestizo nation was born, with the dual legacies of both pre-Hispanic and Spanish culture having shaped Mexico ever since.